Samhain

There is not much that can be said with certainty about the Celtic festival of Samhain. But there are a few things that we know. The Romans wrote about it and of course the Christian missionaries who had come to spread their faith on the British Isles. Samhain is one of four major Celtic festivals that occur throughout the year. Instead of celebrating the solstices and the equinoxes, the Celts seem to have celebrated the points in between those events.

Samhain in Roman Gaul?

The oldest mention of Samhain can be found in the Coligny calendar, a Gaulish peg calendar or parapegma made in Roman Gaul in the 2nd century CE. A parapegma is a calendar or almanac in the form of an inscribed stone on which the days of the month are indicated by movable pegs inserted into bored holes. The Coligny calendar is a bronze tablet of which 73 fragments have been found in Coligny near Lyon, France. It is the most important evidence for the reconstruction of an ancient Celtic calendar. The calendar had been made for five solar years, attempting to synchronize the solar year with the lunar months by inserting intercalary months, since the common lunar year only has 354 or 355 days. So the Coligny calendar has a total of 12 months and there are 29 or 30 days in each month. To make up for the time difference to the solar year, an extra month was added every 2.5 years.

Each of those 12 months is divided into halves. The first half always has 15 days, and the second half either 14 or 15 days. Scholars disagree as to whether the Celtic month began with the new moon, full moon, or the first quarter moon. But we do know that the year of the Coligny calendar began with Samonios. And here is the next scholarly debate: when exactly is Samonios? Some argue that samon is Gaulish for summer. The Roman calendar began the year on 1 January but local calendars started the new year on different dates. The Alexandrian calendar in Egypt, for example, started on 29 August. So it is not inconceivable that the Gaulish year started in summer or any other date, really. So did the year in Roman Gaul start with the summer solstice? The names for the month of June in modern Irish (Meitheamh), Welsh (Mehefin), Cornish (Metheven), and Breton (Mezheven), which are all derived from mediosaminos, "midsummer", might suggest this, but in modern Celtic folklore there is absolutely no precedent for starting the year in summer.

An alternative interpretation is an association with Samhain. The month name Samon[ios] could be related to Samhain. A festival was held during the "three nights of Samonios" (trinux[tion] samo[nii]) on 17 Samonios. The Irish Samhain festival also lasted for 3 nights. Instead of deriving Samonios from Proto-Indo-European *semo- ("summer"), the month's name could also come from the Proto-Celtic *samani- "assembly" and Proto-Indo-European *smHon- "reunion, assembly". Since the Celtic summer ended in July or August, the popular idea that Samhain means "summer's end" is very likely folk etymology.

Yet another interpretation of Samonios is "seed time" or "seed fall". I couldn't find any linguistic derivation for this one, though.

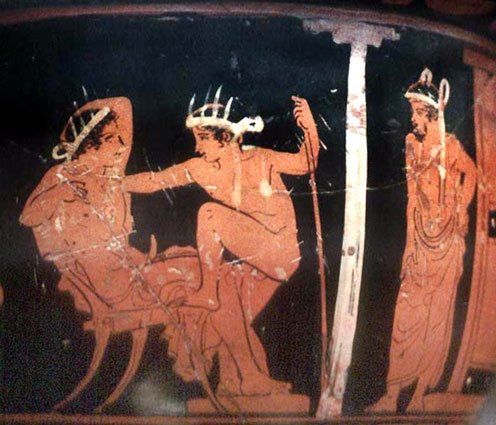

The association of Samonios with the festival of Samhain is supported by an unexpected source: ancient Greece. One of the months in the Coligny Calendar is named Ogronios. Several calendars from Greece in the Roman era have a month named Agrionios, namely Boeotia, Corinth, Epidauros, Rhodos, and the Greek colony on Sicily. From the Boetian festival Agrionia in honour of Dionysos Agrionios, we can deduce that the month of Agrionios corresponds to modern March/April. The Greeks have a significant history of settlement, trade, cultural influence, and armed conflict in the Celtic territory of pre-Roman Gaul, starting from the 6th century BCE. The Gauls borrowed e.g. the Greek symposion or drinking party and made it a part of their own aristocratic feasting customs. If the month of Ogronios is indeed a case of cultural borrowing and corresponds to March/April, then it is reasonable to assume that the year began in November, as Ogronios is the fifth months in the Coligny Calendar. The Gaelic calendar began and still begins in November today.

As with the months, the Gaulish calendar seems to have split the year into two halves: the first beginning with the month Samon[ios] and the second beginning with the month Giamonios. Giamonios is the seventh month and if Samonios is in November, Giamonios would mark the beginning of the summer season. But the name could be related to the word for winter: Proto-Indo-European *g'hei-men-, Latin hiems, Slavic zima, Greek kheimon, Hittite gimmanza. Old Irish gem-adaig means "winter's night". So it's not entirely clear when Samonios and Giamonios begin. But both mark the beginning of a half-year cycle and if Samonios is indeed related to Samhain, the year begins with the dark half of short days and long nights. Since the Gaulish day began and ended at sunset, it would make sense if the Gaulish year also started in darkness.

In De Bello Gallico Julius Caesar notes:

"Spatia omnis temporis non numero dierum, sed noctium finiunt; dies natales et mensum et annorum initia sic obseruant, ut noctem dies subsequatur."

"They define all amounts of time not by the number of days, but by the number of nights; they celebrate birthdays and the beginnings of months and years in such a way that the day is made to follow the night".

But no matter if the month of Samonios actually has anything to do with Samhain: the time of this festival, about midway between the autumnal equinox and the winter solstice, has been important to humans for a long time. It was the time when cattle were brought back down from the summer pastures and when livestock were slaughtered for the winter. Some Neolithic passage tombs in Ireland are aligned with the sunrise around the time of Samhain. It is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature and many important events in Irish mythology happen or begin on Samhain.

Medieval Samhain

In medieval Ireland, Samhain remained the principal festival, celebrated with a great assembly at the royal court in Tara, lasting for three days, consistent with the Gaulish testimony of the "three nights of Samonios". The Hill of Tara is a hill and ancient ceremonial and burial site in Ireland. The earliest written records say that high kings were inaugurated there, and the Senchas Már legal text, written some time after 600 CE, specified that the king must drink ale and symbolically marry the goddess Maeve/Medb as part of the ceremony. The oldest visible monument in Tara is Dumha na nGiall, the "Mound of the Hostages", a Neolithic passage tomb built around 3,200 BCE which has a passage that aligns with the sunrise around the times of Imbolc (the Gaelic festival marking the start of spring) and Samhain. The site also appears in Irish mythology as a battleground and seat of the gods.

Only 20 km (12 miles) from the Hill of Tara lies the Hill of Tlachtga or Hill of Ward. The sacred hill is named after the druidess Tlachtga who died there giving birth to triplets. The major ceremony held at Tlachtga was the lighting of the winter fires at Samhain on November 1. Tlachtga is clearly visible from Tara and the fire lit on the eve of Samhain was a prelude to the Samhain Festival at Tara. Geoffrey Keating, a 17th century historian, claims in the Foras Feasa ar Éirinn that the druids lit a sacred bonfire at Tlachtga and made sacrifices to the gods, sometimes by burning them in the fire. He adds that all other fires were doused and then the cold hearths were re-lit from this bonfire. Scottish Folklorist Florence Marian McNeill says that the traditional way of lighting them was by the friction of one piece of wood on another, or of a rope upon a stake. This "need-fire" is a practice of shepherd peoples to ward off disease from their herds and flocks. It is kindled on occasions of special distress, and the people and the cattle would walk through it or between two fires. Its efficacy is believed to depend on all other fires being extinguished. Samhain was the most dangerous time of the year to be alive: people faced cold weather, long nights, sickness, and hunger. Therefore, this was the time to make offerings to the gods and appease the spirits of the dead and the aos sí ("spirits" or "fairies") with offerings of food and drink to ensure the survival of lifestock, family, and tribe.

According to the Books of Leinster, Ballymote and Lecan, and the Rennes manuscript, human sacrifice was practiced in pre-Christian Ireland. One third of the healthy children were slaughtered to wrest the grain and grass from the powers of nature upon which the tribes and their cattle subsisted. These sacrifices were made on Samhain.

Irish medieval literature tells us that on this night, monsters from the Otherworld and spirits of the dead could walk the earth and mingle with the living. Macgnímartha Finn ("The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn") says that the sídhe, fairy mounds that function as portals to the Otherworld, "were always open at Samhain" and that the High King of Ireland hosted a great gathering at Tara each Samhain. Acallam na Senórach ("Colloquy of the Elders") tells how three female werewolves emerge from the cave of Cruachan (an Otherworld portal) each Samhain and kill livestock. By the fourteenth century "bright folk and fairy hosts" were believed to hold games and feast upon nuts each Samhain at the prehistoric mounds of the Bruigh na Boinne. A number of stories set at the Samhain feast tell of humans being attacked or approached by deities, fairies, or monsters.

Beltane, the Gaelic May Day festival most commonly held on May Eve and May Day at the opening of summer, was regarded in the pastoral areas of the British Isles as a time when fairies and witches were especially active, and magical devices required to guard against them. It seems the same was true for the opening of winter, despite a lack of clear evidence in the early literature alone.

Prehistoric belief in the danger from supernatural forces at the turning of the pastoral seasons and the analogy with May Eve and May Day is so strong that it seems unlikely that all the dread of the night came only from the Christian feast of the dead.

Again with the Calendar

"No man will travel this country," she said, "who hasn't gone sleepless from Samain, when the summer goes to its rest, until Imbolc, when the ewes are milked at spring's beginning; from Imbolc to Beltane at the summer's beginning and from Beltane to Brón Trogain, earth's sorrowing autumn."

The collection of Irish heroic tales known as the Ulster Cycle provides us with the earliest reference to all four of the Irish pagan festivals that marked the changing of the seasons. The character Emer in the 10th-century Tochmarc Emire ("The Wooing of Emer") lists Samhain as the first of these four Celtic quarter days. But the fundamental problem is that writing, Christianity, and the Roman calendar all entered Wales and Ireland as parts of the same process. Therefore, all the earliest written records are going to start the year on 1 January or 25 March in compliance with the Roman fashion. This is at least true of every surviving medieval Welsh calendar. While Ireland was one of the few areas of western Europe not conquered by Rome, the commercial, cultural, and religious influence of Roman Britain (43 to 410 CE) cannot be denied. The Ogham alphabet and writing system was probably first invented in the 4th century at Irish settlements in west Wales and most scholars think it derived from the Latin alphabet. During the reign of the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great (306 to 337 CE), Christianity began to transition to the dominant religion of the Roman Empire and Christian worship had reached pagan Ireland around 400 CE.

To shake things up even further, Germanic season and festival names, like the days of the week, arrived in Britain with the Anglo-Saxon settlers in the 5th century CE. The Northumbrian cleric Bede gives us the earliest description of the English year in 725 CE. In a text on the church calendar, De Temporum Ratione, he tells us that the Anglo-Saxon pagan year was divided into just two seasons, winter and summer. This seems to go with the two halves of the Gaulish calendar too. The English year started at Giuli (Yule) in the middle of winter, and was preceded by a festival known as Modra Nect, Mothers Night.

Christians in the Mediterranean world used to hold a feast in honour of all those who had been martyred under the pagan emperors on 13 May. The feast is mentioned in the Carmina Nisibena of St Ephraem, who died about 373 CE. Pope Boniface IV formally endorsed the May date in the year 609 when he converted the Pantheon, a formerly pagan temple to all of the Roman gods, into a Christian church and consecrated it to St. Mary and the Martyrs on 13 May 609.

By 800 CE churches in England and Germany, which were in touch with each other, were celebrating a festival dedicated to all saints on 1 November, instead. Pope Gregory III changed the official date to 1 November and suppressed the 13 May feast. He was endorsing and adopting a practice which had begun in northern Europe but it had not, as often claimed, started in Ireland, where the Felire of Oengus and the Martyrology of Tallaght prove that the early medieval churches celebrated the feast of All Saints on 20 April.

Samhain and Halloween

Equating Samhain with Halloween or claiming a direct connection between the pagan festival and the modern holiday is as popular today as it was in the 19th century "Celtomania". But the Celts have nothing to do with Halloween says Stefan Moser, director of the Celtic Museum in Hallein, Austria. He sees Halloween as a Christian tradition. There is no evidence that Samhain was originally about death or the dead. But it was a particularly eery time.

In 1589 "hallowmas fires" were forbidden by the presbytery at Stirling. In 1648 the same order was made with respect to Fife by a Kirk Assembly and at Slains, also in Scotland, by the local kirk sessions. A writer in Anglesey during 1741 noted that Hallowe'en coelcerths (bonfires) were "upon the decline". At the same time, traditions we still see in modern observances of Halloween are first documented. One of the earliest references to Halloween mischief, as opposed to Hallowmas fires, is recorded in 1598 in John Stow’s The Survey of London:

These lords [of misrule] beginning their rule on Alhollon eve.

"Souling", the custom of baking and sharing soul cakes for all christened souls, dates back at least as far as the 15th century and was found in parts of England, Flanders, Germany and Austria. People would go from door to door to collect them in exchange for praying for the souls of deceased friends and family. The custom has been suggested as the origin of trick-or-treating. Mumming and guising was part of Samhain from at least the 16th century and was recorded in parts of Ireland, Scotland, Mann and Wales. Since then, it has become a central part of Halloween. Why the costumes are worn has many possible explanations, such as it was done to confuse the spirits or souls who visited the earth or who rose from local graveyards to engage in what was called a Danse Macabre. The Danse Macabre or Dance of Death is an artistic genre of allegory of the Late Middle Ages on the universality of death: no matter one's station in life, the Danse Macabre unites all.

In nineteenth-century Wales Nos Galan Gaea was the year’s most frightening Ysbrydnos (spirit night) and churchyards, stiles, and crossroads were all to be avoided as particular gathering-places for them. The same reputation attended Samhain Eve, Oiche Shamhna, in Ireland, where another name for it was "Puca" Night. Turnips or mangel wurzels were hollowed out to act as lanterns and often carved with grotesque faces. They were also set on windowsills. By those who made them, the lanterns were variously said to represent the spirits or supernatural beings, or were used to ward off evil spirits. These turnip lamps were common in parts of Ireland and the Scottish Highlands into the 20th century when they spread to other parts of England and became generally known as jack-o'-lanterns.

In conclusion, we can say for sure that there was a major pagan festival at the beginning of November which was celebrated, at the very least, in all those parts of the British Isles that relied on a pastoral economy. There is no evidence that it was connected with the dead, and no proof that it opened the year, but it was a time when supernatural forces were especially dangerous and needed to be guarded against or appeased.

It was extremely hard to separate actual attestable sources from often repeated wishful thinking. I hope to have given a genuine and entertaining read on the difficulties and controversies surrounding this holiday. Happy Samhain.

Many thanks to all you good spirits here on Patreon, in particular my demigods, nymphs and satyrs Peter, Vendice, Vladimir, Bill, Jane, Malpertuis, Max, Maxime, and Mike. May evil spirits stay forever clear of your path.

Sources

The Celtic Calendar and the Anglo-Saxon Year by Richard Sermon

Pharsalia by Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, translation by Sir Edward Ridley

The Coligny Calendar by Segomâros Widugeni

The Antikythera Mechanism, an ancient Greek analogue computer

Ancient Greek Religion by Jon D. Mikalson (2010)

The Hill of Tara on wikipedia.org

Time Meddler's Calendarium shows today's date in several historic calendars