Mythology Monday: The Ancient Origins of Easter

This article is an expansion of my #FolkloreThursday Twitter thread on the ancient origins of Easter customs and the mythology surrounding it.

The beginning of spring as a symbol of new life, fertility and rebirth is common in many cultures. After the darkness of winter, nature gains new strength and brings forth new life. There are many stories about gods that die and return to life in the context of the changing seasons. The mythological motif is called the “Dying and Reviving God”. That motif is found in Egyptian mythology in the form of Osiris, who is killed by his brother Seth and revived by Isis, his wife and sister. Because of his death and resurrection, Osiris was associated with the flooding and retreating of the Nile and thus with the yearly growth and death of crops along the Nile valley.

In Greek mythology, Dionysos Zagreus was ripped apart by titans but Athena saved his heart or phallus and Zeus gave it to his lover Semele so Zagreus was reborn as Dionysos. In another version, Rhea or Demeter reassembled his body and revived him, similar to Isis in the Egyptian myth. In another version, Apollon collected the body parts and buried his brother in Delphi. Every year, when Apollon leaves his Oracle for the three winter months, Dionysos resurrects.

Inanna in Mesopotamian mythology descended into and returned from Kur, the ancient Sumerian Underworld. She was saved, but another soul has to take her place. Since her husband Dumuzid did not mourn her, she let him be dragged to the underworld as her replacement. But Inanna has a change of heart and allows him to stay with her in heaven for half the year, explaining the seasons, as without Dumuzid, no wheat could grow.

The Canaan god Baal stayed in the underworld during the dry summer time and his return in autumn was said to cause the storms which revived the land.

Easter Eggs

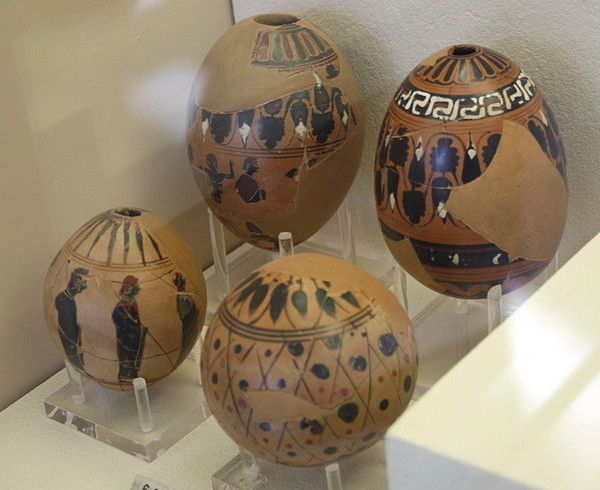

The Christian use of Easter eggs can be traced to early Christians of Mesopotamia and may have been influenced by practices in ancient Egypt, as well as the early cultures of Mesopotamia and Crete. But the practice of decorating eggshells is even older than that: Decorated, engraved ostrich eggs have been found at Diepkloof Rock Shelter in South Africa which are 60,000 years old. You can admire some of the shards here.

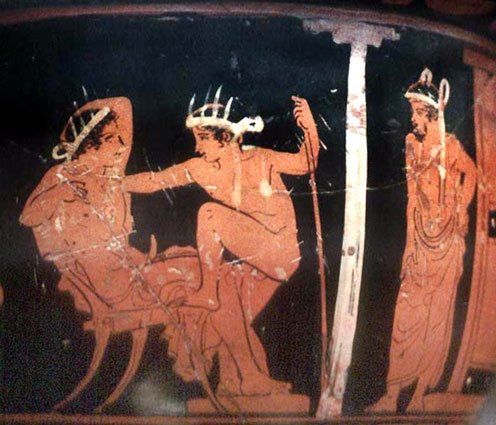

There’s plenty of evidence that the Egyptians, Persians, Greeks and Romans decorated eggs to give as gifts, give to the gods, or even just eat during ancient spring festivals like the Egyptian Sham el Nessim which is still celebrated today, the Greek Anthesteria which honoured Dionysos, and the Roman Lupercalia.

In Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Crete, eggs were already associated with death and rebirth, as well as with kingship. Decorated ostrich eggs, and representations of ostrich eggs in gold and silver or clay, were commonly placed in graves of the ancient Sumerians and Egyptians as early as 5,000 years ago.

Easter Bunny

Rabbits and hares, like eggs, are fertility symbols of antiquity. Early spring is the time when birds lay their eggs and rabbits and hares give birth to large litters, so they became symbols of the rising fertility of the earth at the Vernal Equinox.

In ancient Greece, the hare was associated with Aphrodite and Eros because it was a common gift for a lover and symbolised fertility. It was also associated with Hermes for the same reason because Hermes was a phallic deity occupied with animal husbandry:

"Some say that it was put there by Mercurius [Hermes], and that it had been given the faculty, beyond other kinds of quadrapeds, of being pregnant with new offspring when giving birth to others."

Pseudo-Hyginus, Astronomica, 2nd century CE

The idea that hares bring Easter eggs can be traced back to 17th century Germany, but its roots beyond that are shrouded in mystery. German physician Franck von Franckenau wrote his 1682 doctoral thesis on the Easter egg. He tells us of the folklore that the "Oster-Hase" (Easter hare) hides the eggs in the grass and bushes for children to find. But in other parts of Germany it was a fox, stork or chicken who hid the eggs. But only the hare prevailed, possibly popularised by chocolate manufacturers.

But no matter if it's a religious holiday for you, commemorating the resurrection of Jesus Christ, or a time to enjoy the coming of spring with eggs and bunnies, the celebration of Easter still retains the same spirit of rebirth and renewal as it has for thousands of years.

If you enjoy this blog, please consider supporting me by signing up here or on my shiny new Patreon!