Guest Post: Spirits In Motion – The Wild Hunt

Happy Gaudete Sunday, my lovelies 🕯🕯🕯

Today we are blessed by this guest post by Jürgen Hubert, a #MythologyMonday regular, a weekly hashtag I host on Mastodon. Jürgen knows much more about German folklore than I do, so I am grateful that he agreed to share his vast knowledge with me and my readers. He has been translating a multitude of German folk tale collections in the public domain into English for seven years. Check out the fruits of his labour on “Sunken Castles, Evil Poodles” where he has translated 793 folk tales! He has also published 2 books on German folklore so far, and given the abundance of source material he fully expects to do this long after he has reached retirement age. If you enjoyed this article, find him on Mastodon (also bridged to Bluesky).

Author’s Note: This article focuses primarily on the Wild Hunt phenomenon within German-speaking regions. Links to English-language sources are in bold, while links to German-language sources are in italics.

Spirits in Motion: The Wild Hunt

Imagine yourself wandering through the nighttime countryside of Central Europe of centuries past. The lights of civilization, such as they are, are dim and distant. The noises of human industry are absent, and only the rustling of the trees and the calls of nocturnal animals disturb the silence.

Suddenly, the wind picks up. In the distance you hear strange sounds which gradually come closer and closer. With mounting dread, you hear the clattering of hooves and the baying of hounds.

The Wild Hunt is upon you.

An Attempt At Definition

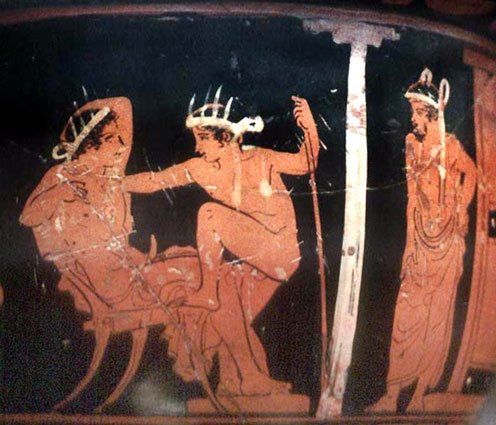

The term “Wild Hunt” conjures up images of a huntsman leading a pack of hounds - but is that truly the essence of this phenomenon? When examining folkloric narratives of the past, it is easy to be misled by modern portrayals of the same narratives. Consider modern werewolf and vampire stories - while we can identify some traces of the earlier folk tales in these stories, they have morphed into something entirely different. The same is true for the Wild Hunt - just because we can open up a mythology encyclopedia (or, heck, Wikipedia) and see images of a Huntsman surrounded by hounds, it doesn’t mean that we should limit ourselves to this particular interpretation. Even the name “Wild Hunt” (“Wilde Jagd”) itself should not constrain us. For instance, in many regions people told of the “Raging Army” instead, yet they were clearly talking about the same overall phenomenon.

And it is important to understand that folkloric phenomena are not naturalistic phenomena. We can provide clear definitions for a thunderstorm, an earthquake, an eclipse, as these are visible, measurable phenomena. Supernatural events and entities reported to us via the oral record, on the other hand, can best be understood as a collection of narrative tropes that might or might not appear in any given story. So it is with ghosts, night hags, dwarves, and so forth - and so it is with the Wild Hunt.

Nevertheless, I would argue that the single defining element of all Wild Hunt narratives is supernatural entities in constant motion. The Wild Hunt rarely rests, and if it does it is never for long. It is compelled to rush onwards from place to place for eternity (or Judgment Day, or some other fated event). This movement is what distinguishes the Wild Hunt from the more common stationary haunts, specters, and monsters which are bound to a particular house, ruin, forest, or mire.

The Leader of the Hunt

A hunt often has a leading hunter - a character with their own personality who can interact with the protagonist of a folk tale in a more personal manner.

The “iconic” and most well-known version of this is Hans von Hackelberg, a court forester at the court of Braunschweig. When he died, he wished that he could hunt forever - and his wish was granted, forcing him to travel the skies with his spectral hounds night after night, year after year. This male figure is often associated with Odin/Wotan, the “All-Father” of Nordic mythology - but if he is indeed an inspiration for the Leader of the Hunt, he is hardly the only one.

For there are female leaders of the Wild Hunt as well. In Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Frau Gauden and her 24 cursed daughters roam the skies. She, too, vowed to hunt forever - but she owes at least as much to the goddess-figure of Hulda/Holle/Perchta as she does to Odin. Near Kyffhäuser Mountain and near Schwarza in Thuringia, it is Frau Holle herself who leads the Wild Hunt. And in the Alps, Perchtel leads a procession of the souls of unbaptized children, who can only be saved from this sad fate if they are given a name.

But storytellers were always willing to swap new people into old roles. In Schleswig, the Danish King Abel haunts the region as punishment for murdering his own brother. Near Sehlde, an expy of Saint Hubertus is cursed to hunt because he killed a sacred stag on Christmas Eve. Meanwhile, in West Pomerania, the Wild Huntsman appears as a dragon - or rather, as a “Drâk”, a fiery spirit that usually presents as a demonic familiar which brings wealth for their masters.

The Hunting Companions

The Leader of the Wild Hunt - if there is a “Leader” - is not alone, but is accompanied by a multitude of other entities. Most famous among these are the hunting dogs, but they are far from the only option.

Widespread is the tale of “Faithful Eckart”, an old man carrying a white staff who heralds the coming of the Wild Hunt and warns people to stay away, lest they come to harm. He is said to have been an advisor to the 4th century king Ermanaric, but how he came to be in the employ of the Wild Hunt, legend does not say.

In Northern Germany, the ghost of a tone-deaf nun heralds the coming of the Wild Hunt in the form of an owl. She is now known as “Hooting Ursel”.

Near Solingen, the Wild Huntsman is accompanied by a “cursed angel”. In Carinthia, the souls of unbaptized children accompany the Wild Hunt as large black night birds. In Styria, the spirits of the Wild Hunt are souls of the evil female cooks of priests - presumably because they frequently tempted the celibate (Catholic) priests away from the path of virtue by serving as their mistresses, or otherwise became a barrier between priests and their congregations.

Predator and Prey

While the leader of the Wild Hunt might have stalked deer, boars, and other ordinary game animals in life, they turn to more disturbing prey once they lead a host of spirits. Their favorite prey are the spirits of the woods, whom they slaughter with abandon. Sometimes they even receive assistance from mortals in such pursuits, or else the mortals hand over these victims out of fear for their own lives. Only carving three crosses into a tree stump could grant these victims a short reprieve.

Mortals who got tangled up in the affairs of the Wild Hunt often suffered for it, especially if they were so foolish as to attract their attention by shouting at them. Sometimes these unfortunates vanished entirely, while at others they had to ride with them for an extended time - or even for eternity.

Luckier were those who merely received a portion of the kill, although they were rarely happy, either. Their share might be a horse haunch, which will pursue them until they consent to eat from them. Worse still are incidents where people receive large pieces of meat from killed forest spirits, which are equally hard to get rid of.

Processions of the Dead

One of the most persistent folkloric beliefs since the dawn of humanity is that the souls of the departed would linger on in this world even after death. Usually they stayed in a single location that was of some significance to them during life, but other ghosts roam the land and hurry from place to place - similar to other Wild Hunt narratives.

In the Valais in Switzerland, the ghosts follow the “Ridge Trains” - secret paths that wind through the High Alps, from graveyard to graveyard, wearing only clothes that they owned in life and which were given away to the needy. No one knows their ultimate destination, but those who cross their routes at the wrong moment fall ill.

Likewise in Switzerland, in the Aargau Canon, there is a ghostly funeral procession that winds its way through the Hallwil valley. After these souls made a mockery of a funeral in life, they are now condemned to repeat it in death, year after year.

And on the many-storied Untersberg mountain near the Austrian-German border, the souls of the departed can be seen in the vicinity of the quarries that produced the famous Untersberg marble.

The Night Parades

There are also supernatural processions of entities who might not be ghosts, but demons or even stranger entities. In the Untersberg region, armies of dwarves were on the march. In Vorarlberg in Austria, the Night Folk moved from town to town under the din of fantastic music. Sometimes even the Devil can be found in their midst, turning musicians into masters of their craft if they stand their ground.

Witches, too, can form their own processions, riding on broomsticks and oven forks and stranger implements. Their traditional night for a gathering is Walpurgis Night (the eve of May Day), when they can be witnessed rushing through the air. In other tales, they travel in disguised forms, such as a huge mob of cats racing towards Brocken Mountain.

Singular Monsters

Usually the Wild Hunt appears as a group of spirits, but some entities are capable of representing the Wild Hunt all by themselves.

The Night Raven is a massive black bird with iron wings that also accompanies the Wild Hunt from time to time - although it also roams around on its own, at a speed that would make a fighter jet proud. It, too, shares its kill with those who call after it.

In Tyrol, the Wildg’fahr (“Wild Roaming”) is often portrayed as a mountain demon that can take all sorts of forms - a fleshless, eight-legged horse, a fiery hog, a whirlwind, a rapidly-moving wagon with black birds perched on it (this form has also been reported on the Untersberg).

The Turning of the Years

Just like witches gather during Walpurgis Night, the Wild Hunt likewise is particularly prominent during a certain time of the year: The “Rauhnächte” (“Hairy Nights”), which are also known as the “Twelve Nights of Christmas” in the English world. This period lasts from Christmas Day (December 25th) to Epiphany (January 6th). It is a “time between the years”, when the old year is ending but the new year has not yet fully arrived. During such a threshold period, spirits roam the land. In many parts of Austria, it is custom that people disguised as monsters form a procession through villages. And Frau Holla checks on the women in a household to see if they have been diligent in spinning flax.

Thus, it is not surprising that Frau Gauden and other incarnations of the Wild Hunt favor this season as well - and so does Santa Claus, their modern-day successor. But the Wild Hunt can and does appear at any time of the year, even if they favor the nights after Yuletide.

Elsewhere and Everywhere

The Wild Hunt is usually discussed as a phenomenon of European folklore. But shorn of its specific European cultural and religious trappings, is this narrative truly unique to Europe?

In Japan, the Hyakki Yagyō (“Night Parade of One Hundred Demons”) is a procession of spirits that marches or riots through the streets of Japan on summer nights, and mortals who come across them will come to harm unless protected by the right blessings. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

In Hawai’i, the Nightmarchers are the ghosts of ancient warriors who march from their burial sites to old battlefields throughout the night accompanied by the beat of drums and music made with conch shells. Are they really so different from the phantom armies of Europe?

Jacob Grimm first developed the scholarly framework for understanding the “Wild Hunt” concept in his 1835 treaties “Teutonic Mythology”. He quickly tied this to Odin of Norse Mythology, and while he discusses alternative narratives, such as the female Wild Hunt leaders of the Hulda/Holle/Perchta myth-complex, it is this Norse interpretation which became the most popular among the German Romantic Nationalists of the 19th century, and their latter-day heirs.

But to me, this focus on Odin and Norse influences is overly reductive. Ultimately, the Wild Hunt narrative derives from a near-universal human experience - the fear of being alone in the wilds at night, and hearing strange noises one cannot identify. And as usual, folk storytellers took such universal human experiences, and filled them with their own stories - using whatever narrative tropes were available to them, and each storyteller came up with their own interpretation.

Thus, we might see faint traces of Odin in Hans von Hackelberg, and stronger ones of Hulda in Frau Gauden. But the Wild Hunt is bigger than any single of its inspirations, and cannot be tied to any single origin. It lurks wherever humans fear the dark in the wild places of the world - in Europe and elsewhere.

Further reading: For further discussion of the Wild Hunt and its various incarnations, I recommend “Phantom Armies of the Night” by Claude Lecouteux.

Find Jürgen's translated German folk tales on sunkencastles.com and give him a follow on Mastodon 💖