Pagan Midwinter Festivals

You voted for "Pagan Festivals around the time of the Winter Solstice" to be December's non-fiction article and here it is! 🥳

The year's shortest day lies at the heart of midwinter celebrations around the world. As you will see, winter solstice festivals are not particular to any one religion nor time and place.

The winter solstice, also known as midwinter, happens twice a year: in the Northern hemisphere in December and in the Southern hemisphere in June. It's the time of the North or South pole's maximum tilt away from the sun. The winter solstice itself lasts only a moment, but its occurrence marks the day with the shortest period of daylight and the longest night of the year.

The solstice seems to have been a significant moment even during Neolithic times: the primary axes of Stonehenge in England and Newgrange in Ireland have been carefully aligned to the winter solstice sunrise (Newgrange) and the winter solstice sunset (Stonehenge). Some Egyptian temples are aligned to the winter solstice sunrise as well and there are festivals celebrating this event on every continent. I will focus on the ancient Mediterranean but you will find festivals from other parts of the world as well.

Saturnalia

The Roman Saturnalia was originally a farmer's festival to mark the end of the autumn planting season. It was held in honour of Saturnus in his function as a titan god of agriculture. Titus Livius (Livy) tells us that the festival was established in 496 BCE when the Temple of Saturnus in the Forum Romanum in Rome was dedicated. But there is evidence that it is much older.

The Saturnalia used to be celebrated on a single day, on December 19. But the festival became so popular that it expanded to a whole week. The date was moved with the Julian calendar reform to "sixteen days before the Kalends of January" which is December 17. Saturnalia was a dies festus, a legal holiday when no public business could be conducted.

As an agricultural festival, Saturnalia doesn't have anything to do with the winter solstice. But no matter the solstice, people had great fun at the Saturnalia! The official rituals to Saturnus ended with a public banquet and the celebrants would shout the holiday greeting "Io Saturnalia" to everyone they met in the streets, akin to wishing each other a "Merry Christmas" or "Happy Holidays" nowadays. The following days were filled with feasting and fun while the strict Roman social rules were lifted and gambling was allowed, culminating in the Sigallaria on the last day of the Saturnalia (December 23) with the exchange of gifts. Common gifts were small wax or terracotta figurines but Martial names a whole variety of Saturnalia gifts: writing tablets, dice, knucklebones, moneyboxes, combs, toothpicks, a hat, a lyre, a hunting knife, oil lamps, perfumes, pipes, a pig, a parrot, a Priapus made of pastry, wine cups, and spoons.

Two days after the end of Saturnalia, on December 25th, the Romans observed the birthday of the major imperial deity Sol Invictus:

Sol Invictus

Following Saturnalia, on December 25 the renewal of light and coming of a new year was celebrated as Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the "Birthday of the Unconquered Sun".

Like Mithraism, the cult of Sol Invictus was introduced from the East and Sol was often equated with Mithras. On 25 December 274 CE, Imperator Aurelian dedicated a new temple for Sol Invictus ("Unconquered Sun") and made the worship of the sun god an official cult but the cult of Sol had existed in Rome since the early Republic (traditionally dated to 509 – 27 BCE).

In 321 CE, Imperator Constantine the Great who decreed that, with an exception for farmers, Sunday was to be a day of rest:

On the venerable Day of the Sun let the magistrates and people residing in cities rest, and let all workshops be closed.

But the first mention of the festival Dies Natalis Solis Invicti on 25 December doesn't appear until 354 CE in the calendar or "Chronography" of Furius Dionysius Philocalus. Of course it may have been celebrated before that, but we don't have any solid evidence. The same calendar also mentions the birthday of Jesus as an annual feast day:

MENSIS DECEMBER VIII·KAL·IAN N·INVICTI·CM·XXX

Eighth day before the kalends of January = On December 25: Birthday of the Unconquered, games ordered, thirty races

ITEM DEPOSITIO MARTIRVM VIII·KA·IAN Natus Christus in Betleem Iudeae.

On December 25: Birth of Christ in Bethlehem Judea

We actually have the first mention of 25 December as the birthday of Jesus before that, but this is the first reference to a holiday or feast day being celebrated.

In the Julian calendar used at the time, December 25 marked the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, after which the days begin to lengthen. Whether this date was specifically selected to celebrate the solstice is uncertain because ironically the cult of the Sun in pagan Rome did not celebrate any of the other quarter-tense days.

The last inscription referring to Sol Invictus dates to 387 CE, and there were enough devotees in the fifth century that the Christian theologian Augustine found it necessary to preach against them. Sol Invictus played a prominent role in the Mithraic mysteries, and was equated with Mithras.

Christmas in Pagan Rome

Hippolytus, a younger contemporary of Clement of Alexandria, stated in 235 CE that Jesus was born nine months after the anniversary of the creation of the world, which Hippolytus believed to have been on March 25 (Chronicon, 686ff). The Nativity thus would be on December 25. According to Jewish belief, great men were born and died on the same day and thus lived a whole number of years without fractions. Jesus was therefore considered to have been conceived on March 25, as he died on March 25.

Around 350 CE Pope Julius I declared December 25 as the official date of the birth of Jesus, documented in a sermon by Ioannes Chrysostomos titled "On the Birthday of our Savior Jesus Christ".

In 380 CE, Nicene Christianity became the official state religion of the Roman Empire and official support for all other creeds and cults ended.

Brumalia

The Saturnalia did continue to be celebrated as Brumalia until the Christian era, when its festivities were becoming absorbed in the celebration of Christmas.

Brumalia was an ancient Roman, winter solstice festival honouring Saturnus, Ceres, and Bacchus. The festival included night-time feasting, drinking, and merriment. Despite the 6th century emperor Justinian's official repression of paganism, the holiday was celebrated at least until the 11th century in the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, as recorded by Christopher of Mytilene.

According to Varro's De Lingua Latina, the name Brumalia derives from bruma, "the shortest day," winter solstice:

Bruma is so named, because then the day is brevissimus 'shortest'....The time from the bruma until the sun returns to the bruma, is called an annus 'year'....The first part of this time is the hiems 'winter'.

Vitruvius also writes:

This time from the shortness of the days, is called Bruma (winter) and the days Brumales.

John the Lydian describes in his 6th century work "De Mensibus" that farmers would sacrifice pigs to Saturnus and Ceres on Brumalia, while vine-growers would sacrifice goats in honour of Bacchus because the goat is an enemy of the vine and they would skin them, fill the skin-bags with air and jump on them.

Civic officials would bring offerings of firstfruits (including wine, olive oil, grain, and honey) to the priests of Ceres.

At that time, until the Waxing of the Light, ceasing from work, the Romans would greet each other with words of good omen at night, saying in their ancestral tongue: "Vives annos"—that is, "Live for years".

Haloa

Haloa was celebrated in in the region of Attika in ancient Greece. The word derives either from "threshing-floor" or "garden" and is a festival about the first fruits of the harvest, not the winter solstice, even though it took place every year during the month of Poseidon, which corresponds roughly to December and January. The ancient Greeks don't seem to have celebrated the winter solstice at all.

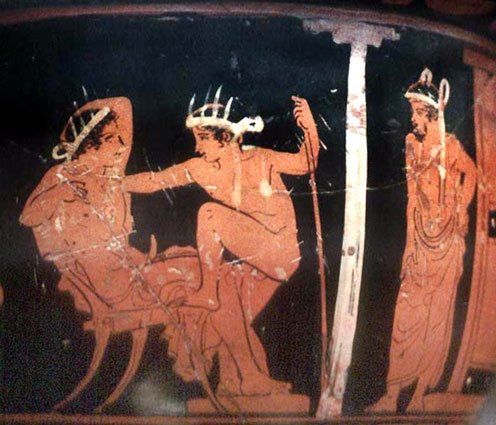

Only little is known about the specifics of this festival, but we do know that it honoured Demeter and Dionysos. It was celebrated with a feast with genitalia-shaped cakes, but without the foods forbidden in the Eleusinian Mysteries like eg pomegranates. All women were expected to attend this event while men were almost always excluded. But the men had a legal and moral expectation to pay for their wives' expenses in these festivities. According the the satirist Lukian of Samosata, Dionysos punished the shepherds who killed his friend Ikarios by taking the form of a beautiful maiden and maddening them with sexual desire. But when the maiden suddenly disappeared, the shepherds' erections wouldn't go down until an oracle told them that they must placate Dionysos by fashioning genitals out of clay and dedicating them to the gods. This dedication thus became a custom of the festival, so after the feast was over, the women danced around a giant phallus, leaving it offerings and engaging in ritual obscenity. It was a festival of "lusty words" and activities with the consumption of lots of wine and pornographic confectionery celebrated by the women alone so that "they might have perfect freedom of speech" and could make all kinds of "unseemly quips and jests".

The Birthday of Horus

In ancient Egypt, the birthday of the god Horus was said to be on the winter solstice:

...Isis, when she perceived that she was pregnant, put upon herself an amulet on the sixth day of the month Phaophi; and about the time of the winter solstice she gave birth to Harpocrates, imperfect and premature, amid the early flowers and shoots. For this reason they bring to him as an offering the first-fruits of growing lentils, and the days of his birth they celebrate after the spring equinox.

Harpokrates is the Hellenised form of Hor-pa-khered, meaning Horus the Child. The child Horus, personifies the newborn sun each day and the winter sun after the solstice.

Hae autem aetatum diversitates ad solem referuntur, ut parvulus videatur hiemali solstitio, qualem Aegyptii proferunt ex adyto die certa, quod tunc brevissimo die veluti parvus et infans videatur: exinde autem procedentibus augmentis aequinoctio vernali similiter atque adolescentis adipiscitur vires, figuraque iuvenis ornatur: postea statuitur eius aetas plenissima effigie barbae solstitio aestivo, quo tempore summum sui consequitur augmentum: exinde per diminutiones veluti senescenti quarta forma deus figuratur.

I did not find an English translation of Macrobius' Saturnalia that is freely available. Part of the text is translated on some blogs as

…at the winter solstice, the sun would seem to be a little child like that which the Egyptians bring forth from a shrine on the appointed day, since the day is then at its shortest and the god is accordingly shown as a tiny infant.

My Latin is not good enough to provide my own translation but the text does mention not only the winter solstice ("hiemali solsticio") but the vernal equinox and summer solstice as well, comparing the sun on those dates to the stages of life in a human (infancy, adolescence, senescence). It does not, however, mention Horus by name.

But it seems several ancient Egyptian temples and monuments are oriented toward the winter solstice sunrise: Hatshepsut's mortuary temple at Deir El Bahari, Montuhotep's mortuary temple at Deir El Bahari, the mortuary temple of Amenhotep III at Qurna, the mortuary temple of Amenhotep I at Deir Medina, and the Temple of Horus on Thoth Hill on the West Bank at Luxor.

Şeva Zistanê

Şeva Zistanê, the Night of Winter, is an unofficial holiday celebrated on the winter solstice by communities throughout the Kurdistan region in the Middle East, encompassing parts of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran.

The Night of Winter is considered one of the oldest holidays still observed by modern Kurds and was already celebrated by ancient tribes in the region. Since the night is the longest in the year, the ancient tribes believed that it was the night before a victory of light over darkness and signified a rebirth of the Sun.

The Night of Winter is assumed to be the night when the evil spirit is at the peak of his strength. The following day is celebratory as it is believed that God and his angels have claimed victory. Since the days are getting longer and the nights shorter, this day marks the victory of light, or the sun, over the darkness or evil.

Today, many families prepare large feasts for their communities and the children play games and are given sweets in similar fashion to modern Halloween practices.

Shab-e Yalda or Shab-e Chelleh

Shab-e Yalda, Yalda Night, or Shab-e Chelleh, Night of Forty, is an Iranian festival celebrated on the "longest and darkest night of the year".

Yalda is a winter solstice celebration on the night between the last day of the month Azar and the first day of the month Dey in the Iranian civil calendar. The date corresponds to the night of December 20/21 (±1) in the Gregorian calendar.

Yalda Night marks the night between the last day of autumn and the first day of winter. In ancient times, people considered winter to consist of two parts, each forty nights long. Yalda Night was the beginning of the "big Chelleh", the first forty nights of winter, from which its other name Shab-e Chelleh derives.

The name 'Yaldā' for this festival is actually a loan word from Syriac-speaking Christians: Yalda literally means "birth" in Syriac, an Aramaic dialect. But in a religious context, it was also the proper name for Christmas. As we discussed above, Christmas fell nine months after Annunciation and was thus celebrated on the eve of the winter solstice too. The Christian name for their festival passed to the non-Christian neighbours and although it is not clear when and where the Syriac term was borrowed into Persian, gradually 'Shab-e Yalda' and 'Shab-e Chelleh' became synonymous and the two are now used interchangeably.

In Zoroastrian tradition the longest and darkest night of the year was a particularly inauspicious day, and the customs of what is now known as Shab-e Chelleh were originally intended to protect people from evil during that long night, at which time the evil forces of Ahriman, the destructive spirit, were imagined to be at their peak. People were advised to stay awake most of the night, lest misfortune should befall them, and they would gather in the safety of groups of friends and relatives, share the last remaining fruits from the summer, and find ways to pass the long night together in good company to eat, drink and read poetry (especially Hafez) until well after midnight. Fruits and nuts are eaten and pomegranates and watermelons are particularly significant. The red color in these fruits symbolizes the crimson hues of dawn and glow of life. Prior to the prevalence of electricity, decorating and lighting the house and yard with candles was also part of the tradition.

The word yalda, cognate with the Arabic yelda meaning 'dark night' might be related to the Old Norse jól and Old English geōl – yule.

Yule and Modra Nicht

If you read my article on Samhain, you may remember the English year started at Giuli (Yule) in the middle of winter, and was preceded by a festival known as Modra Nicht, Mothers Night.Mōdraniht or Modranicht is Old English for "Night of the Mothers" or "Mothers' Night". It was an event held at what is now Christmas Eve by the Anglo-Saxon Pagans. The event is attested by the medieval English historian Bede in his 725 CE work De Temporum Ratione:

Incipiebant autem annum ab octavo Calendarum Januariarum die, ubi nunc natale Domini celebramus. Et ipsam noctem nunc nobis sacrosanctum, tunc gentili vocabulo Modranicht, id est, matrum noctem, appellabant, ob causam, ut suspicamur. ceremoniarum quas in ea pervigiles agebant.

They [the English] began the year on the 8th kalends of January [25 December], when we celebrate the birth of the Lord. That very night, which we hold so sacred, they used to call by the heathen word , that is "mother's night", because (we suspect) of the ceremonies they enacted all that night.

Romano-Germanic votive inscriptions to matrons could have something to do with Bede's Modranicht. Altar stones from the former Roman province of Germania Inferior were dedicated to native mother goddesses called Matrae or Matronae ("mothers" or "matrons") who often occur as triple deities, and are thought to have bestowed fertility and protection on the people or region after which they were named. Similar altars have been found throughout Northern Italy, France, Spain and Britain, where the goddesses often have Celtic names. Likewise, in Germania Inferior many of the goddesses appear to have Germanic names, such as the Matribus Suebi (Swabian Mothers) found on altar stones from Cologne, and the Matronae Vacallinehae (Mothers of the Vacalli) who were worshipped at the temple site of Pesch in the northern Eifel.

The Latin inscriptions are formulaic with the goddesses’ name being followed by the name of the person making the dedication, and then a series of standard phrases like pro se et suis (for himself and his family), ex imperio ipsarum (by their command) and votum solvit libens merito (my vow fulfilled willingly and deservedly):

Matronis Austriahenabus Q(uintus) Atilius Gemellus v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito).

Depictions of the Matrae and Matronae include sacrifice like burning incense, pigs, and bowls filled with fruit—and decorations of fruits, plants and trees. In most cases, the votive stones and altars are not found singularly, but rather in groups around temple buildings and cult centers.

The term for "sacrifice" in Norse paganism is blót. A blót usually consisted of animals or war prisoners, in particular pigs and horses. The meat was boiled in large cooking pits with heated stones, either indoors or outdoors. The blood was considered to contain special powers and it was sprinkled on the statues of the gods, on the walls and on the participants themselves.

The great midwinter blót called Jól (or Yule), a very important sacrifice, was celebrated some time after Winter solstice. When Christianity arrived in Scandinavia, the yuleblót / winterblót was celebrated on 12 January after the Julian calendar.

A special toast was reserved for the celebration of Jól: "til árs ok friðar" — "for a good year and peace".

Makara Sankranti

Makara Sankranti or Maghi, is a Hindu festival day dedicated to the sun deity Surya. It is observed each year in January and celebrates the first day of the sun's transit into Makara (Capricorn), marking the end of the month with the winter solstice called Pausha in the lunar calendar and Dhanu in the solar calendar. The festival celebrates the first month with consistently longer days.

The date of Makara Sankranti is set by the solar cycle of the Hindu lunisolar calendar, and is observed in the solar month of Makara and the lunar month of Magha, which is why the festival is also called Magha Sankranti. The festival takes place on a day which usually falls on 14 January of the Gregorian calendar, but sometimes on 15 January because the Sun comes to the same location 20 minutes late every year, which means the Sun needs one day extra after every 72 years.

Makara Sankranti is observed with social festivities such as colorful decorations, rural children going from house to house singing and asking for treats (or pocket money), melas (fairs), dances, kite flying, bonfires and feasts.

Dongzhi Festival

The Dōngzhì Festival, literally: 'the extreme of winter', is one of the most important Chinese and East Asian festivals celebrated by the Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans on or around December 22. The traditional East Asian calendars divide a year into 24 solar terms. Dōngzhì is the 22nd solar term, and marks the winter solstice. It begins when the Sun reaches the celestial longitude of 270°.

In China, Dongzhi was originally celebrated as an end-of-harvest festival. Today, it is observed with a family reunion over the long night, when tangyuan are made and eaten together. Tangyuan are balls made of glutinous rice flour that are eaten in sweet broth. They can be white or brightly coloured. Each family member receives at least one large tangyuan in addition to several small ones. The round shape of the balls and the bowls where they are served, come to symbolise the family togetherness and prosperity. Old traditions also require people to gather at their ancestral temples to worship on this day. There is always a grand reunion dinner following the sacrificial ceremony.

The festive food is also a reminder that the celebrators are now a year older and should behave better in the coming year. Even today, many Chinese around the world, especially the elderly, still insist that one is "a year older" right after the Dongzhi celebration instead of waiting for the lunar new year.

Willkakuti

Willkakuti, Return of the Sun, is an Aymara celebration in the Andes highlands of Bolivia, Chile, and Southern Peru which commemorates the winter solstice in the Southern Hemisphere. It marks the New Year of the Andean peoples and the beginning of the new agriculture cycle. Therefore Machaq Mara, New Year, is another name for the festival.

When Spanish conquistadores colonised South America in the 16th century, they banned the Aymaran Willakakuti festival and replaced it with the Gregorian calender and New Year's on 01 January.

But recently, Willakakuti is getting a revival! Despite freezing temperatures, thousands of people gather at the ancient Temple of Kalasasaya (200 BCE to 200 CE) to watch the sunrise on the day of the winter solstice to the sound of drums and quenas. The temple was used to identify the change of seasons and the solar year of 365 days. In both equinoxes (21 March and 21 September) the Sun went through the centre of the main entrance gate, which can be accessed through a large stairway. On the winter solstice, the Sun was rises in the Northeast corner of the gate.

According to the Aymara calendar, the Return of the Sun will be celebrated in June 2020 for the 5528th time. It was declared a national holiday in Bolivia in 2009.

This year, the Northern winter solstice takes place on 22 December at 04:19 am Universal Time. What are you doing on this longest (or shortest) night of the year?

Io Saturnalia and live for years my lovely demigods, satyrs and nymphs Ellis, Jane, Malpertuis, Max, Maxime, Mike, Peter, Sarah, Vendice, and Vladimir. May your days be merry and bright!

A special shout out goes to my very first titan, Bryce. May Sol Invictus brighten your heart during the longest of nights and bring you joy and success for the next year ☀️

Sources

Saturnalia by James Grout, University of Chicago

Io, Saturnalia! by Carole of Following Hadrian

Sol Invictus - The Imperial Sun Cult on tertullian.org

Sol Invictus and Christmas by James Grout, University of Chicago

Chronography of 354 on tertullian.org

De Mensibus, Book IV by John the Lydian

Isis, Horus, and the Holy Day of December 25th on isiopolis.com

Plutarch's Moralia, Isis and Osiris, Chapter 65 (Loeb) on wikisource.org

Saturnalia by Macrobius (Latin)

Hatshepsut's Mortuary Temple: Winter Solstice Alignment at Deir El Bahari by David Furlong

Dongzhi (solar term) on wikipedia.org

Bolivia celebrará el Año Nuevo Andino 2019 en Chataquila, Los Tiempos 17 June 2019

Kalasasaya on wikipedia.org (Spanish)