Artist Spotlight: The Life and Works of Sappho

This article is brought to you by my patrons on Patreon. Many thanks to Bill, Jane, John, Malpertuis, Max, Peter, and Vendice for pledging $5 or more. May lovely-robed Aphrodite forever be your ally.

Patrons and paid subscribers get early access to my articles and stories and can read longer works that I don't publish for free. They can also make fiction prompt wishes.

Sign up today!

The Life and Works of Sappho

Very little is known about Sappho's life and of her body of work only a few hundred lines with one or two complete poems survive. And yet her beautiful poetry captivates readers even 2500 years after her death.

Sappho was born around 630 BCE on the island of Lesbos, and her passionate love poems to women inspired the modern words "sapphic" and "lesbian". If you read any of my books, chances are high you already know that the Greek verb lesbiazein doesn't refer to sex between women but to fellatio. In the ancient world, women from Lesbos were not famous for their love for other women but for their beauty and enthusiasm for sex.

There is one exception by fellow lyric poet Anakréōn (born ca. 582 BCE):

Again golden-haired Eros strikes me

with a purple ball, and calls for me to play

with the girl with the fancy sandals.

But she, since she's from well-built

Lesbos, finds fault with my hair

(since it is white) and gapes

at another (girl).

Anakréōn 358

So that Lesbian girl at least seems to prefer other girls to old men with white hair.

Sappho's Life

Just as with modern poets, the love poems of Sappho are not a biography of her love life. They are still fiction, designed to give the reader an erotic experience. Therefore, one should be cautious when considering her poetry as a biographical source.

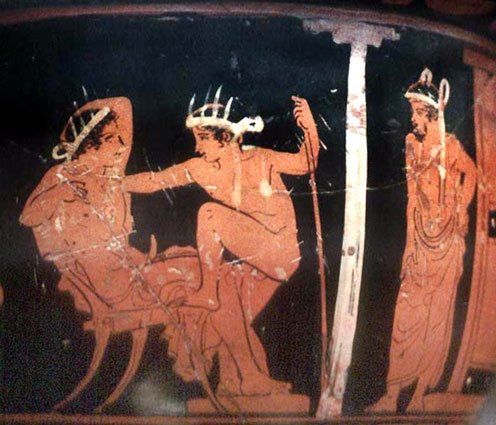

We cannot say for sure how this brilliant woman looked like as no contemporary portraits survive. All we have today are numerous conceptions of both ancient and modern artists. In fragment 58 of her poetry, she describes her hair as white but formerly black or dark (melaina):

[You for] the fragrant-blossomed Muses’ lovely gifts

[be zealous,] girls, [and the] clear melodious lyre:

[but my once tender] body old age now

[has seized;] my hair’s turned [white] instead of black;

Obviously, dark hair is not unusual in the Mediterranean. What should also not be surprising given her education is that Sappho was born into a wealthy aristocratic family. Greek writer Athenaios claims in the 3rd century CE that she often praised her brother Larichos for pouring wine in the town hall of Mytilene, an office held only by sons of the best families. This is consistent with the environments that she describes in her verses. Hēródotos (*490 BCE), who was born over 100 years after her, reports in his "Histories" that another brother, Charaxos, ransomed the Egyptian courtesan Rhodopsis for a large sum of money and that Sappho criticised him for this in one of her poems.

Some time between 604 - 591 BCE, Sappho and her family were exiled from Lesbos and moved to Syracuse in Sicily. Her family's involvement with the conflicts between political elites on Lesbos may have been the reason, as this was the reason for exiling fellow poet Alkaios' from Mytilene around the same time. All of them were later allowed to return to Lesbos.

Sappho may or may not have had a daughter named Kleïs. She refers to Kleïs in two fragments of her poems but some scholars suggest that her use of the word pais, "child", may be intended to mean eromenos, "beloved". The eromenos is the younger partner in the traditional relationship between an adolescent boy and an adult man. This makes it difficult to discern whether Sappho is using "child" as an endearment for a younger person, if she's talking about an actual daughter, or a younger lover.

Speaking of which...

Sappho's Love for Women

Scholars have made several attempts to hide or deny Sappho's love poetry aimed at other women, the most blatant of which changed the gender of the addressee.

Others use later biographies of Sappho that claim she fell in love with a ferryman named Phaon and killed herself by jumping off the Leukadian cliffs to be rid of her desire. But the lengthy and detailed account of people who jumped from Cape Leukas related by the mythographer Ptolemaios Chennos (ca. 100 CE), never mentions neither Sappho nor Phaon at all. Greek historian and geographer Strabon (ca. 64 BCE) specifically disclaims that Sappho was the first to take the plunge at Leukas. Another alleged husband is mentioned by Soudas with the name Kerkylas of Andros. The translation of the name makes apparent that it was invented by a comic poet: kerkos is a word for the penis and Andros is a Greek island as well as the word for man. Say hello to Sappho's husband Penis of Man.

Why her poetry expressed erotic desire for women if she was only attracted to men was explained by saying she addressed her poems to women because she was taking on the persona of a male love poet. I personally had considered this possibility, that she was taking on a male persona, before I read her poetry. This hypothesis falls apart as soon as you read Sappho's "Ode to Aphrodite". The speaker in this poem is Sappho herself and the sex of Sappho's beloved is established, even if only from a single word, as female (εθελοισα / etheloisa). In an attempt to "rescue" Sappho from devious homosexuality, translations in the 1850s changed 'etheloisa' (a noun, nominative singular feminine) to 3rd person plural 'ethelousan' making the love interest a man and both of them unable to restrain themselves.

Lovely-robed deathless Aphrodite,

crafty-waeving child of Zeus, I beg you,

do not tame my spirit with pains

or anguish, queen,

but come here, if ever before

you heard my voice from a distance

and listened, and leaving the house

of your father, you came

having yoked your golden chariot.

And the beautiful swift sparrows led you

over the dark earth, swiftly whirling their wings

through heaven's air,

and straightaway you arrived. But you, blessed one,

with a smile on your immortal face

asked what again I suffered and why again

I was calling,

and what exactly I want to happen

with my crazy heart. "Whom again must I persuade

to lead you into her affection? Who, Sappho,

is doing you wrong?

For if indeed she flees, swiftly she will pursue;

if she does refuse gifts, soon she shall give them;

and if she does not love, swiftly she will love

even if she does not wish to."

Come to me again now, and free me from harsh

sorrow, and whatever my heart desires to happen,

make it happen. And you yourself

be my ally.

Listen to the original ancient Greek version performed by my Twitter friend Bettina Joy de Guzman:

British classicist Denys Page divorces Sappho's work completely from her person, saying: "Though her poetry shows us her inclinations, there is no evidence that she ever acted on them."

While it is true that the speaker in a poem (or any fiction) should not be equated with the author, and it is also true that no evidence for a love affair between Sappho and another woman survives, I personally find it hard to believe that a woman who is attracted to women and lives in a society that doesn't stigmatise same sex love, would never act on her desires.

More long-lasting than any of the other attempts to explain away Sappho's love for women was the 19th century invention of Sappho as a school mistress.

This hypothesis assumes that young aristocratic women were sent to Sappho to be tutored before entering the adult world of marriage. The resulting teacher-student relationship likens her love affairs to the mentorship of a (male) lover with his eromenos. But there is no evidence for such a school.

So, was Sappho a lesbian or not? If we define 'lesbian' as a woman who loves other women, the answer is yes. The ancient Greeks did not have a concept of sexual orientation like we have today. They probably did not think of a woman's desire for another woman as a different kind of desire than a man's for a woman or a woman's for a man or a man's for a youth. Love, it seems, was love.

Sappho's Career

Ancient authors agree that Sappho was remarkable - but not because of her attraction to women. In fact, ancient sources make no mention of it. Female homoeroticism may have come as a shock to Victorian scholars, but women enjoying sex together wasn't news to the ancient Greeks.

Plato called her "the tenth Muse" and she was also given the epithet "The Poetess" just like Homer was "The Poet". Sappho was one of the nine lyric poets most highly esteemed by scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria, the intellectual and cultural center of the ancient world. Her poetry was well-known and greatly admired through much of antiquity and she was widely regarded as one of the greatest lyric poets. Lyric poetry was intended to be performed accompanied by the lyre (hence the name). They were meant to be sung. My Twitter friend Bettina Joy de Guzman reconstructs ancient Greek (and Latin) music and plays it on historical instruments while she sings the original ancient Greek lyrics. Listen to her performance of Sappho's Invocation to Aphrodite here.

Sappho was a prolific writer. It is estimated that she composed around 10,000 lines in her lifetime. Further, she was an innovator, as she was one of the first poets to write in the first person, making the experience personal and individual.

She is also said to have invented the schema of the four-line stanzas and they are named "Sapphic stanza" because of that. It is not clear if she really created it or if it was already part of lyric tradition on Lesbos. Her most famous poem in the Sapphic stanza is "Sappho 31", written in the Aeolic Greek dialect of her home island of Lesbos:

That man seems like a god to me

whoever is sitting opposite you

and hears you nearby

speaking sweetly.

And your desirable laughter, which sets aflutter

my heart in my breast.

For when I look at you, even for a moment, no speaking

is left in me.

No: my tongue breaks, silently, and thin

fire is racing under my skin

and no sight in my eyes and drumming

fills my ears

and cold sweat holds me and shaking

seizes all of me, and greener than grass

I am. Dead — or almost

so I seem to me.

But all must be endured, because even a person of poverty...

Her poetry is unmatched in beauty. But not all were fans of Sappho.

The second century CE Roman author Apuleius specifically remarks on the "strangeness" of her Aeolic Greek dialect. She was a popular character in ancient Athenian comedy, where she was caricatured as a promiscuous woman. At least six separate comedies called "Sappho" are known. While her poetry was still admired in the ancient world during the Roman period, critics found her lustful and her homoerotic desire a problem. Horace called her mascula Sappho in his Epistles, which the later Porphyrio commented was "either because she is famous for her poetry, in which men more often excel, or because she is maligned for having been a tribas". A tribas, from the Greek word tribein, to rub, is a "masculine woman" who takes the (manly) active role in sex, usually with another woman.

By the third century CE, the difference between Sappho's esteemed literary reputation as a poet and her poor moral reputation as a woman had become so significant that the suggestion that there were in fact two Sapphos began to develop. In his "Varia Historia", Claudius Aelianus (ca. 175 – 235 CE) wrote that there was "another Sappho, a courtesan, not a poetess".

The early Christians didn't favour The Poetess much either. Tatian of Adiabene (ca. 120 - 180 CE), an Assyrian Christian and theologian, wrote in his "Address to the Greeks":

"This Sappho is a sex-crazed whore who sings of her own wantonness; but all our women are chaste, and the maidens at their distaffs sing of divine things more nobly than that damsel of yours."

According to legend, Sappho's poetry was lost because the church disapproved of her morals. By the twelfth century, Ioannis Tzetzes wrote that "the passage of time has destroyed Sappho and her works". Around 1550, Italian mathematician Jerome Cardan wrote that Gregory Nazianzen, Archbishop of Constantinople in the 4th century CE, had Sappho's work publicly destroyed, and at the end of the sixteenth century Joseph Justus Scaliger claimed that Sappho's works were burned in Rome and Constantinople in 1073 on the orders of Pope Gregory VII.

But no matter the haters, Sappho's poetry is still considered extraordinary and her works continue to influence other writers to this day.

I end with one of my favourites of Sappho's poems:

...Sardis [the capital city of Lydia]

often turning her thoughts here

...you like a goddess

and in your song most of all she rejoiced.

But now she stands out among Lydian women

as sometimes at sunset

rosyfingered Selene [the moon]

surpasses all the stars. And her light

stretches over salt sea

equally and flowerdeep fields.

And the beautiful dew is poured out

and roses bloom and frail

chervil and flowering sweetclover.

But she goes back and forth remembering

gentle Atthis [a woman's name] and in longing [himeros, sexual desire]

she bites her tender mind.

Sappho 96

Sources

- Controlling Desires. Sexuality in ancient Greece and Rome by Kirk Ormand

- Sex and Sexuality in Classical Athens by James Robson

- Sappho's Invocation to Aphrodite, music, vocals, and lyre by Bettina Joy de Guzman

- Sappho's Poems (including the original Greek)

- Wikipedia article on Sappho Fragment 1: Ode to Aphrodite

- Translations and the Text: To Aphrodite

- Sappho Fragment 1: text and commentary on digitalsappho.org

- Sappho's Hymn to Aphrodite: translation, notes, and comments by Elizabeth Vandiver

- Poems of Sappho, translated by Julia Dubnoff

- Roman Receptions of Sappho

- Sappho 94

- Tatian's Address to the Greeks, Chapter 33. Vindication of Christian Women

None of these are affiliate links and I'm not making any money off any purchases.